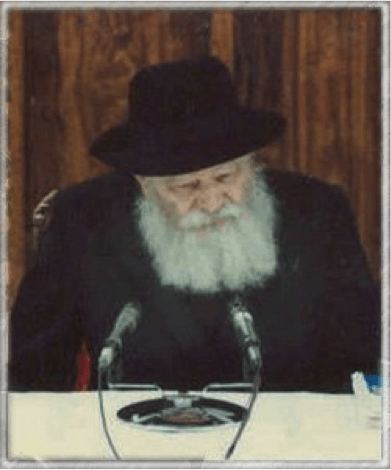

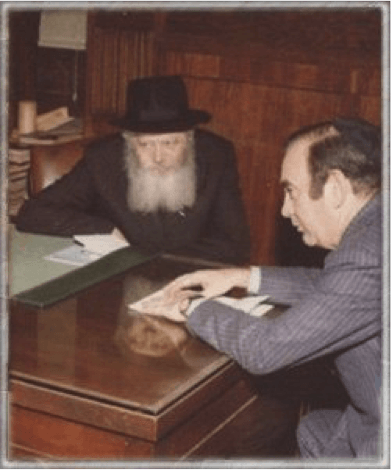

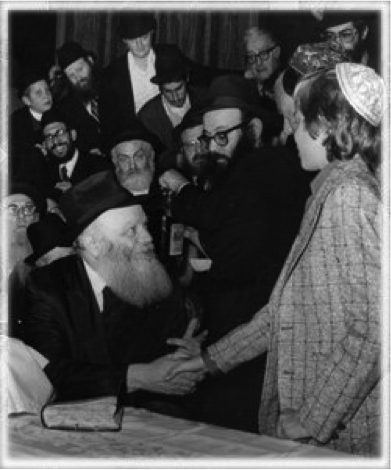

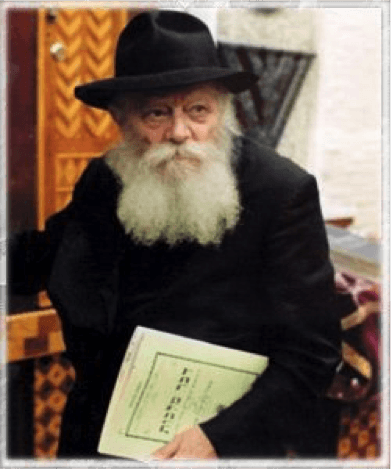

The Rebbe

For over 50 years RABBI MENACHEM MENDEL SCHNEERSOHN, affectionately known by Jews throughout the world simply as “the Rebbe” (literally my teacher my spiritual inspiration), successfully inspired our generation to be excited for and work together towards the long awaited arrival of Moshiach. We present you below a glimpse into the Rebbes life and his teachings. Discover a life of empathy leadership and a touch of the miraculous.

The Chassidic Approach

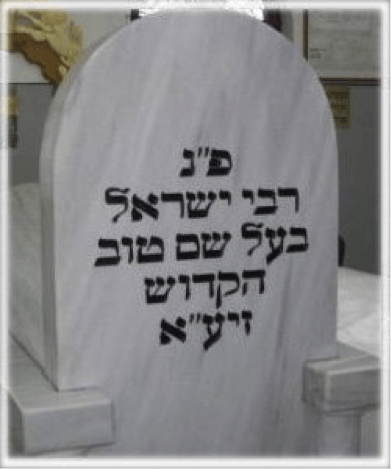

To begin telling the story of the Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, we must go back to the origins of contemporary Chassidism and the life of its founder, Rabbi Israel Baal Shem Tov (also known by the acronym “Besht,” 1698-1760).

To begin telling the story of the Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, we must go back to the origins of contemporary Chassidism and the life of its founder, Rabbi Israel Baal Shem Tov (also known by the acronym “Besht,” 1698-1760).

The Besht was an extraordinary tzaddik who possessed miraculous powers. Tales about him and his teachings spread through Eastern Europe during the fifth and sixth decades of the eighteenth century. Hundreds, and later thousands of people in cities, towns, and remote villages became his enthusiastic followers. Many of the rabbinical authorities were suspicious of the new movement, and followed its progress with considerable alarm. They were puzzled and frightened by the movement’s unorthodox approach to a number of traditional Jewish issues. In addition, the Besht challenged the arrogant attitude of some rabbis and Torah experts, who tended to treat the simple, uninformed Jewish masses with disdain and ridicule.

At that time the Jews, dispersed throughout the vastness of Eastern Europe, were mired in bottomless despair and confusion. The tragic repercussions of the dismal episode of Shabbtai Tzvi, the false messiah, coupled with the horrible massacres of Khmielnitsky’s Cossacks, resulting in nearly half a million Jewish victims, were still fresh in people’s memories. A vast number of Jewish families lived in unspeakable poverty; burdened by constant hunger, people began to neglect the most basic age-old traditions such as the duty to teach their children the Torah. Many felt that they had lost their guiding light and the timeless Jewish sense of a sacred duty in this world. For them, the Besht came as a wellspring of vital energy, which would relieve the unbearable pain of their souls. He taught that the Almighty is best served through joy and cheer, helping people regain their lost faith, encouraging them to put their unconditional trust in the Creator. He exalted the pure and unsophisticated faith of the simple Jew, rekindling a sense of self-respect. According to the Baal Shem Tov, the Lord does not draw a distinction between a simple, uneducated Jew who believes and observes the commandments wholeheartedly, and the greatest of sages versed in the intricacies of the Torah. According to the Baal Shem Tov, in the eyes of G*d, pure intentions, simple faith and a kind heart are fully as important as learning.

These ideas disturbed and frightened the rabbis who were concerned about losing their status. However, the new movement continued to grow and expand, drawing Jews in ever-increasing numbers. Most of them were simple, penniless folk who found in the new teaching their own way of serving G*d, but an impressive number of prominent scholars and great Torah experts joined the Besht as well.

The rapid spread of Chassidism among countless thousands of Jews from every walk of life was due to a large extent to the unique personality of the Besht himself. He had an exemplary way of serving the Almighty with heartfelt joy and selfless love for his Jewish brethren. Even in his teens, when the Besht was a teacher’s assistant at a children’s Talmud Torah, he impressed everyone not only with his piety and modesty, but also with the strength of his love for each and every Jew.

The Chassidic teaching expounded by the Besht attached supreme value to every word of prayer, but more than that, to the thoughts and feelings fuelled by these words. The singing and dancing associated with Chassidic gatherings serve not only as a means of bonding and unifying, but are also used as a special way of serving G*d. Singing and dancing as a means of achieving communion with the Almighty was not invented by the Chassidim. Rabbi Yitzchak (Isaac) Luria (known as The Holy Ari, 1534-1572) lived in Tzfat in the Land of Israel two hundred years before the Besht, and entered the annals of Jewish history as one of the greatest scholars and teachers of Kabbalah (the “hidden,” mystical aspect of Torah). He was known to pray with his followers in nature, where prayer was combined with dancing and singing. However, it was the Besht who elevated dancing and singing to the level of worship and higher spirituality. Moreover, Chassidim believe that a Chassidic melody, more than any other mode of worship, is capable of raising us above our dismal worldly reality, allowing us to reach the highest spiritual realms.

Chassidic composers (many of whom were rabbis themselves) not only wrote new music but also adapted songs, military marches, and shepherd’s tunes of the people in whose midst they lived. Chassidism views singing not as a mere source of esthetic pleasure or entertainment, but rather as a means of attaining a higher spiritual state, a refined mode of feeling that helps reveal the presence of the invisible Creator.

The intense emotions inspired by Chassidism are depicted in the following tale. An illiterate shepherd boy somehow found himself at the Besht’s synagogue on the holy day of Yom Kippur. Suddenly, his soul overflowed with sublime exaltation. He felt an intense desire to commune with the Almighty, but he did not know how to pray! After his lonely years in the pastures, he was more accustomed to the voice of animals and birds than to human speech. Overcome by spiritual turmoil, he ran to the Holy Ark containing the Torah scrolls, and burst out in a long, heart-rending “cock-a-doodle-do.” The indignant worshippers rushed at the boy, but the Besht embraced and kissed him, saying that his simple-heartedness had opened the hitherto impregnable heavenly gates, and his peculiar prayer had overtaken those of the other congregants and reached the Almighty.

The text of Chassidic prayers deviated slightly from mainstream traditions. The differences stemmed mainly from the teachings of the Holy Ari. Slight changes were also introduced in some of the customs. However, all of these changes concerned nuances only, and definitely did not impinge on the letter and spirit of the Torah – both Written and Oral – or the commandments. The Besht would tell his followers that a single verse from the psalms of David, if it is read with zeal and sincere devotion, is capable of changing the course of the entire universe.

During his wanderings, the Baal Shem Tov would greet every Jew he met with, “How are you?” or “How is everything?” Hearing the reply, “Fine, thank G*d!” made him rejoice in the knowledge that he had enabled another Jew to praise the Almighty. “Our Heavenly Father hates sadness and rejoices when His children are happy,” the Besht would say.

Stories about the wondrous deeds and miracles performed by the Besht passed by word of mouth, telling about his fatherly concern for all Jews. An increasing number of Jews became convinced that the Besht was the greatest tzaddik, whose prayers and pleas were received by the Almighty with particular favor. Before long, these stories appeared in print, spreading rapidly through towns and villages. They told about the Besht’s ability to heal body and soul, about his amazing advice. Those who followed his counsel achieved prosperity, avoided dangers, and found good husbands for their daughters. Oppressed by enmity and hatred, destitute, dispirited by hard work and hand-to mouth existence, people found consolation and hope in these stories. Thousands of people flocked to the Besht in search of counsel, guidance and blessings.

As the Besht’s popularity increased, as the people’s love for him grew, and as his influence continued to expand, the fury of his adversaries grew more intense. They hurled the most absurd accusations against him, but the Besht had nothing to hide and nothing to apologize for. He traveled, surrounded by his Chassidim, through towns and villages, appearing in synagogues, on the streets, in market squares. He drew inspiration from nature, in which he saw the ever-present hand of the Creator. Sometimes he would withdraw into nature, finding spiritual sustenance in solitude. On frequent occasions, however, he went walking through fields and forests together with his numerous students. They joined in fervent prayers, submerging their minds in the clear refreshing waters of Torah, listening to their mentor without fear of their enemies’ suspicious glances. The Besht did not intimidate his audience with threats of punishment for their sins, unlike the numerous self-styled “preachers” of that time, who would occasionally work their listeners into fainting spells. On the contrary, like a loving father, the Besht strove to bring Jews closer to the Almighty through the power of love and care. He did not deliver lengthy sermons filled with casuistic sophistries; he would present the most profound and complex religious concepts in the form of allegories, stories and real life situations – a method that characterizes Chassidism to this day.

Most of the Baal Shem Tov’s teachings were transmitted orally. Very few written records have reached us. One surviving letter, dated 1752, addressed to his brother in-law, describes a dream or a vision in which the Besht encounters Mashiach. The episode described in the letter took place five years earlier, in 1747. The Besht asked Mashiach, “When, Master, will you come?” The reply was, “When your wellsprings spread to the outside,” meaning, when the Besht’s teachings spread to those who have not yet been touched by them. Therefore, these teachings were intended from the very start to hasten the coming of Mashiach, to bring about the kingdom of goodness and light. As we have already pointed out, in no way did his ideas alter the content and essence of Torah; all they did was to shift the emphasis, particularly regarding the ways a Jew may serve G*d. According to an eloquent Chassidic saying, it is far more effective to spread the light than to waste energy fighting the darkness. One tiny candle will banish darkness from a huge room.

The Besht strenuously opposed self-torture, mortification of the flesh, or any other practice designed to suppress the natural life of the body. He cautioned the Chassidim against the numerous fasts popular at the time as a means of earning G*d’s favor. As the Baal Shem Tov taught, “A Jew must have not only a strong spirit but a strong body as well, so that he may serve G*d with his entire being.”

The Besht left this world in 1760. By that time, the Chassidic movement had reached immense proportions, and the number of its followers continued to increase. The numerous disciples of the Besht carried his teachings to the Jewish masses in Eastern Europe. These teachings were presented both as colorful, heart-warming tales about the miraculous deeds performed by the Besht, and in the form of writings that systematically expounded his views. As a result, the Besht’s teachings continued to spread in ever-expanding circles with each passing year and with every generation.

The stories told about the Baal Shem Tov are permeated with boundless love for the simple, the pure of heart, and for every Jew. These stories have not only become firmly entrenched in the daily lives of Chassidim; they are part of the heritage of all Eastern European Jews. With their message of hope and confidence, they help people bear the burdens of everyday life, and allay the endless fears facing Jews in their alien environment. Melaveh Malkah, the festive meal held after Shabbat to usher out the Sabbath Queen, was a particularly propitious time for sharing stories about the Besht and other righteous men.

The stories about the Besht reveal a fairy tale-like world of virtue, generosity and spirituality, their warmth thawing the hearts of contemporary Jews, which have been frozen by the chilling brutality of today’s world. Some of these stories are extremely short. Here is one example.

A Chassid came to the Besht and burst into bitter tears. “Rebbe, Rebbe, what am I to do? My own son has strayed from the path of true righteousness!” The Besht blessed the Chassid and said, “Love him, my son … ” With a heavy sigh, the Chassid insisted, “Oh Rebbe, he has already fallen so low!” To which the Besht replied, “Then love him even more!”

The following is a typical longer story about the Baal Shem Tov. Once there was a prosperous, urban Jew named Reb Chaim. He had heard a great deal about the Baal Shem Tov and the incredible miracles he had performed, but Reb Chaim saw no reason to take a long journey just for the sake of meeting the great sage in person. After all, he was a very busy man, and moreover, his affairs were going so well that there was no need to ask the tzaddik for help or advice. Yet the first-hand accounts of the Besht’s miraculous powers eventually had their effect, and the man decided to go, if only to satisfy his curiosity.

After Reb Chaim told the Besht about himself, his family and his business, the tzaddik asked him whether he was in need of any help or advice. The man replied that he was doing just fine, praise G*d, and that he needed neither help nor advice, but naturally, like any other Jew, he would like to have the tzaddik’s blessing. The Besht blessed Chaim, and then asked him for a small favor: to deliver a letter from the Besht to Reb Tzaddok, the treasurer of one of the synagogues in Chaim’s city. Upon his return, Chaim plunged back into the hustle and bustle of his affairs, and totally forgot about the Besht’s request. He continued to prosper as before. However, a few years later his business floundered, and his profits began to dwindle. After several more years, he declared bankruptcy and sank into abject poverty. Once, while rummaging through a pile of old clothing in the hope of finding a mislaid coin, he came across the letter addressed by the Besht to the synagogue treasurer, Reb Tzaddok. Chaim was aghast at his oversight. Sixteen years had passed since the Baal Shem Tov had entrusted him with the letter, and during that time the Besht had left this world. Naturally, Chaim rushed off to look for Reb Tzaddok, and in one of the city’s synagogues he found a treasurer by that name. Together they opened the letter. In it, Reb Tzaddok was told that the bearer of the letter was a formerly wealthy businessman who had gone bankrupt, and the Besht asked Reb Tzaddok to lend the man a large sum of money to help him restore his fortune, payoff his debts, and make generous donations to worthy causes as he had done in the past. To substantiate his message, the Besht informed Reb Tzaddok that precisely at the time of Chaim’ s visit, Reb Tzaddok’s wife, who had been childless for many years, would bear him a son. Chaim and Tzaddok had barely finished reading the Besht’s letter when Tzaddok’s neighbors burst into the synagogue with happy news: his wife had just given birth to a boy.

Hundreds of stories recount the way the Baal Shem Tov taught his Chassidim to value true compassion, generosity and good deeds. According to these stories, the Besht was gifted with the ability to explain his lessons not only verbally but visually as well, revealing the repulsive nature of arrogant and conceited people and the beauty and nobility of those who are kind hearted and devoted to their fellow human beings. He contrasted the virtues of kindness and self-abnegation with indifference and vanity. Afterwards he asked each person present to place his hands on the shoulders of those sitting next to him on either side. The Besht himself would do the same, closing the human circle. Next, the Baal Shem Tov would tell the people to close their eyes. A mysterious force would then begin to flow through the human ring, and people would cry out in surprise at the vivid visual impact of what they had just heard. The people he had admonished looked loathsome and pitiful in this amazing vision, while those he had praised appeared in the fullness of their radiant nobility.

There were murmurs of discontent among some of the Besht’s more educated Chassidim because the Besht treated simple pious people with enormous love, and many innkeepers, craftsmen, and small merchants became his devoted followers. The Baal Shem Tov was in the habit of sending his educated Chassidim to just such simple, unpretentious people to learn genuine, unwavering faith in G*d and love for their fellow Jews.

One Shabbat, these simple guests were given special attention by the Besht during the first Shabbat meal on Friday evening. For one, he would pour wine from his own cup over which he had pronounced the blessing; to another, he would hand a piece of the challah; with the third, he would share a piece of fish from his own plate. The Besht’s closest disciples, people well versed in the Torah, were amazed by their teacher’s behavior.

The Baal Shem Tov had a custom to invite his Shabbat guests to the tish (the ceremonial Friday night meal which the Besht conducted in the company of his Chassidim), as well as to the third Shabbat meal held in the late afternoon.

At the second meal, however, only his closest disciples would gather at the table. Other guests were not even allowed to watch from afar what took place in the house. They were to have their second Shabbat meal wherever they lodged for the night, and afterwards to come to the Besht’s synagogue. There these simple, largely uneducated people worshipped the Almighty the only way they knew how: by purifying and sanctifying their hearts as they chanted verses from Psalms.

Taking his usual place at the head of the table during the second Shabbat meal, the Baal Shem Tov bid his pupils to sit in their regular places, as was his practice. He began to speak, revealing mysteries of Torah that filled their hearts with indescribable joy. The Besht also experienced moments of spiritual rapture, and the disciples thanked the Creator for granting them the privilege of being close to this great man. Yet some of the students could not help having critical thoughts. Why is their mentor showing such respect to common, ignorant folk incapable of understanding his words?

Suddenly the Besht’s face grew solemn. In a strained voice, his eyes shut, he said, “Even the most righteous men are unworthy of standing in the place occupied by repentant sinners. Our sages say there are two ways of serving the Creator: one is the way of the righteous, the second, the way of ba’alei teshuvah. The devotion of the common people belongs to this second level, the highest level of repentant sinners, for they experience feelings of abasement, of regret for their flawed past, and they sincerely strive to do everything in their power to improve in the future.”

A quiet, entrancing melody swept through everyone gathered at the table; those of the pupils who had been skeptical about the correctness of their teacher’s conduct realized that he knew their innermost thoughts. The melody swelled. The Baal Shem Tov opened his eyes, gave a long and intense look at each of his disciples, and told them to place their right hand on the shoulder of their neighbor. After they had done that, the Baal Shem Tov asked them to close their eyes and not to open them until he told them to. Then he placed his right hand on the shoulder of the person sitting to his right, and his left on the shoulder of the person sitting to his left. The circle was closed.

From that moment on, they could “see” the simple Jews praying in the synagogue, and hear the moving melodies carrying their heartfelt prayers.

“Ribono shel olam! Lord of the Universe!” a man’s voice rang out, appealing to the Creator in words that came straight from his heart. Then the same voice pronounced the words originally spoken by King David, “Bechaneini, HaShem! Test me, 0 Lord! Cleanse my heart!”

“Zisser Foter! Beloved Father!” cried out another man, who was reciting words from Psalms, “Choneini, Elokim, choneini! Be merciful unto me, Oh G*d; be merciful unto me for my soul trusts in Thee; yes, I will take refuge in the shadow of Thy wings until these calamities have passed.”

“Heavenly Father!” came the beseeching moan of a soul that was being tossed from side to side by a storm, desperately searching for the saving anchor. “Gam tzippor matz’ah bayit, for even a bird has found shelter, a sparrow a nest for itself.”

The wise and holy Chassidim felt a shiver as they listened to these words from the Psalms, these heartfelt prayers. Their eyes were closed, but tears of repentance were flowing from behind their lowered lids. They envied those simple people, whose worship of the Creator consisted solely of their straightforward reading of the Psalms.

The Baal Shem Tov removed his hands from the shoulders of his disciples, and the vision and the melody faded away. The teacher told them to open their eyes, and they joined in a quiet song.

Among those present at that Shabbat meal was Rabbi Dov Ber, the Maggid of Mezherich. Years later, he told his disciple, Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liady, that he felt greater rapturous love for the Almighty at that moment than ever before. His entire being had been seized by a passionate desire not just to repent, but to do full teshuvah – to return to what a Jew is meant to be, to return to Jewish destiny.

The singing came to an end. The disciples sat silent, lost in contemplation. For a while, the Baal Shem Tov continued to sit with his eyes shut. Then he looked at the Chassidim and said, “The music you heard is the pure sound of simple people praying in synagogues. They recite verses from the Psalms, using them to express the innermost depths of their souls. We mortal humans have a body that prevents us from approaching the truth, and a soul that embodies a particle of the truth, for the soul is part of the One Who is Truth itself. Thus, even though we are creatures in whom the truth is embodied only in part, we are nevertheless called sefat emet, ‘the edge of truth,’ beings who have touched the truth. Even though we are imperfect, we are capable of recognizing and feeling the truth, and of being stunned by it. How much more strongly, then, must the Almighty – who is the absolute Truth – feel the truth in the psalms sung by these simple people!”

For a long time after that, the Maggid of Mezherich told Rabbi Shneur Zalman, he felt anguish over having doubted whether the Baal Shem Tov was right to embrace the common people. He subjected himself to various punishments in an attempt to expiate his sin, yet nothing helped, until one night he had a vision that brought peace to his soul. In one of the palaces in the Garden of Eden, little children sat around the table studying the Torah. At the head of the table sat Moshe Rabbeinu. They were studying the passage that discusses the apparent lack of faith shown by our forefather Avraham upon hearing the Almighty promise him that he and his wife would have a son even though they were old. One of the children read in a loud voice, “And Avraham prostrated himself, and laughed, and said in his heart, ‘How can a hundred-year-old beget a son?”’ Moshe explained that all the commentaries used in Midrash to elucidate this verse are certainly valid. At the same time, every sentence in the Torah also has a straightforward meaning. The question of how our forefather Avraham could have conceivably doubted G*d’s words may be answered as follows: the doubts arose because Avraham had a body – and even a holy body is corporeal.

When the Maggid heard that by the very fact of being made of flesh and blood, people are prey to doubts and skepticism, no matter how irreproachable their conduct, he was freed of the painful memories of his doubts concerning his Rebbe’s actions. He had finally found the answer.

In stories about the Besht, he is presented as a loving father of the ordinary people, the poor and the hungry. In reality, however, the Besht was not surrounded only by common people. His circle included people from all walks of life, from every level of Jewish learning, including great Torah scholars. Nor it is accurate to say that people were driven to the Baal Shem Tov solely by despair and calamity. Many of his followers came from the top echelons of society, drawn by the wisdom of his teachings, the magic force of his personality and his good deeds. Many of those who joined the Besht happily surrendered their high social standing for this privilege. A vivid example of this is Rabbi Ya’akov Yosef of Polonnoye, who recorded and published much of what he had heard from the Baal Shem Tov.

The Baal Shem Tov is commonly acknowledged to be the embodiment of the perfect tzaddik, one who is considered by the Talmudic sages to be capable of attaining the highest rung in the hierarchy of spiritual realms, accompanied by the Shechinah (the Divine Presence). All the prominent Chassidic leaders of the subsequent generations were tzaddikim, serving as intermediaries between the Almighty and humans, and guiding their Chassidim both in spiritual devotion and in everyday life. Devotion to the tzaddik and absolute conviction that he possesses unique powers bestowed by the Almighty are among the fundamental tenets of Chassidism. At a superficial glance, it would appear that these beliefs separate Chassidism from other currents in Judaism. In fact, the concept of the tzaddik is deeply entrenched in Judaism and the Torah, and it is frequently encountered both in the sayings of the Talmudic sages and in the Kabbalah, i.e., nearly two thousand years before the birth of modem Chassidism. Faith in the righteous man was a widespread phenomenon not only during the Talmudic era, but even much earlier. In our daily prayers we quote the biblical chapter that reflects this belief even during the Jewish Exodus from Egypt: “And the people believed the Lord and His servant Moshe.”

However, modem Chassidism formed a new social framework with the tzaddik at its nucleus. The tzaddik performs the functions of a large, wide-ranging organization, even though he has no “weapons of power,” either physical or economic, apart from his extraordinary spiritual energy and boundless love for every Jew, reciprocated by his followers’ devotion to him and his teachings.

The Besht had a unique capacity to reconcile the unimaginably high status of the tzaddik with the ability to descend to the level of the common people, helping them not only in their spiritual efforts, but also in material, mundane matters. In this, he represented the perfect embodiment of one of the basic precepts of Torah: “All Jews are responsible for one another.”

In addition to serving the Almighty with joy and gladness, the vital importance of “following one’s heart,” of openness and simplicity – qualities which we have already discussed and which are described in every book on Chassidism – the Besht’s teachings have other components that touch on the philosophical dimension, and are as deep as the sea. Of primary importance in this regard are the concepts of Permanent Creation and absolute, unlimited Divine Providence (whereby the tiniest event or motion in the universe is determined directly by G*d).

The Besht derived the idea of Permanent Creation from the verses: “Your word, Oh Lord, is eternal; it stands firm in the heavens,” and “He, in His Goodness, every day constantly renews the act of Creation.” The Besht explains that G*d’s creation of the world was not a one-time act. It is inconceivable that having created the world, the Almighty would detach Himself, as it were, leaving His creatures to lead an independent existence. Creation is not comparable to objects fashioned by a craftsman, which, once created, have no further need of the artist’s intervention. Human hands create something from something, matter from matter; only the form is changed. Divine Creation fashions something from nothing (ex nihilo), bringing the very substance of the object into existence. Thus it is impossible for the work of creation to stop even for a moment, for were that to happen, the entire world would cease to exist and all created matter would revert to a state of “nothingness.” This purely rational conclusion is based on logical analysis of the mysteries of creation, an act perceived by the human mind as fashioning “something material” out of a spiritual, intangible entity. Therefore G*d’s utterance, “Let there be a firmament” is an ongoing, endless process of continually recreating the firmament anew each moment. This applies to Earth and to everything contained thereon.

From here, it is but a short step to the idea of Divine Providence. If, as we have seen, the existence of every object depends on G*d’s continual act of creation, it follows that no event – no matter how miniscule – can take place unless willed by G*d. Thus, according to the Baal Shem Tov, even “a leaf cannot fall from a tree unless it be G*d’s will.” G*d’s supervision of the world extends to even the tiniest, seemingly trivial details, so that G*d determines not only the act and the timing of a leaf s fall, but also the way it falls – whether face up or face down.

Similarly, Divine Providence applies to human beings and everything that happens to them. This does not contradict the notion of free will, which the Almighty has granted to every human being. When a Jew has to decide between observing a commandment and committing a sin, he is totally free to make his choice. G*d does not force him to choose one or the other. At the same time, when a Jew decides to move, let us say, from one place to another, there is a hidden purpose to his decision. Heaven directs his steps so as to enable him to perform good deeds and virtuous acts. A Jew, wherever he may be, must conduct himself in keeping with his divine calling, always striving to recognize his purpose and to act accordingly.

It should be stressed once again that the Besht did not introduce any “innovations” or changes in Torah or in Judaism. The concepts of caring for one’s neighbor, of loving one’s fellow Jew, as well as of serving G*d with one’s entire heart, are deeply rooted in Judaism since time immemorial. Even in his incredibly profound philosophical ideas, the Besht did not deviate an iota from the traditional Torah viewpoint. These ideas, though deeply rooted in Torah, had not been sufficiently emphasized, and thus had not been fully integrated into mainstream Jewish philosophy. All the Besht did was to shift the emphasis, highlighting the importance of these concepts. In addition, he identified practical ways of making these concepts the cornerstone of everyday Jewish life.

The following story illustrates another fundamental tenet of the Besht’s teachings and actions: unwavering belief that the Almighty is always there to help.

For a time, the Baal Shem Tov lived in the mountains, not far from the small town of Kuty, earning his livelihood by digging for clay and selling it to the locals. Once, he wished to buy a copy of a fundamental text of Kabbalah, the Zohar, but he had no money.

While unloading his cart filled with clay next to the house of Reb Moshe, the rabbi of Kuty, the Baal Shem Tov asked to borrow his copy of the Zohar. Reb Moshe, who was known for his kind heart, did not ask any superfluous questions or inquire why this clay digger needed the Zohar. He went into the house and came out carrying the book. The Baal Shem Tov took the book, kissed it, and said that he would leave his cart there in the yard, while he went to pray at the synagogue.

Clutching the book in his arms, the Baal Shem Tov ran through the narrow streets, trying to make sure that the town people would not notice the Zohar in the hands of a simple clay-digger. Suddenly, he stumbled into a cart being driven by none other than his brother-in-law, Reb Gershon from Brody. The Baal Shem Tov gripped the book tightly under his arm.

“Israel!” called out Reb Gershon. “What is that book you are holding?”

The Baal Shem Tov was silent. Reb Gershon got down from the cart, took the book, and gave the Baal Shem Tov a look of disapproval. “Israel! Is this what you need in your life? The Zohar?

Reb Gershon kept the book that the Baal Shem Tov had dreamt of studying. The Baal Shem Tov headed to the synagogue with a heavy heart, dejected by his loss. In the synagogue, he stood next to the stove and began to pray with mournful sighs.

Some time later, Reb Moshe also entered the synagogue and heard the sighs of the same clay digger who had been so happy and excited when he had given him the Zohar. Reb Moshe approached the Baal Shem Tov and asked him why he was sighing. At first, the Besht refused to answer, but, under Reb Moshe’s persistent questioning, he finally said, “I am sighing because of two things. First, because the mezuzah attached to the synagogue entrance contains an error. Secondly, because the Zohar has been taken away from me. However, I am absolutely sure that the Almighty will respond to my prayer, and that somehow I will get this book, which I need so much.”

Reb Moshe immediately checked the mezuzah, and discovered that it did indeed contain an error. Next he went to the bookcase, pulled out a second copy of the Zohar, and handed it to the Baal Shem Tov. “This is a present for you!” He also blessed the Baal Shem Tov, “May you be spared another meeting with Reb Gershon.”

Reb Moshe was deeply impressed by the Baal Shem Tov’s ability to detect a mistake in the mezuzahwithout opening it, and by his profound faith in the Almighty. He prayed with joy, and as he reached the words, “Blessed is he who trusts G*d, and G*d will be his pillar of strength,” he even danced. He swore never to forget this incident, which would always remind him of boundless faith in G*d. The Baal Shem Tov, on his part, swore never to forget Reb Moshe’s kindness, and that the latter would always remain his friend.

Several years went by. Reb Moshe was told that the Baal Shem Tov was dabbling in magic charms, strange customs and similar dubious practices. Reb Moshe was hurt; it was he, after all, who had given the Baal Shem Tov his first copy of the Zohar.

Meanwhile, the rabbi of Kuty was informed that the magnate who owned the neighboring town of Gorodenka had arrested the Jew who leased his inn for failing to pay his rent on time. Moreover, he had arrested the man’s entire family – his wife and children – and was going to baptize the children by force.

Reb Moshe sent an urgent letter to the Baal Shem Tov, for he knew that the latter had experience ransoming captive Jews. In his letter, he urged him to do what he could to free the prisoners. Upon receiving the letter, the Baal Shem Tov and his disciples set out at once for Gorodenka. On the way, he recounted to his companions the virtues of the rabbi of Kuty, and how he had given him the Zoharwhen he was too poor to buy it.

The Baal Shem Tov succeeded in persuading the magnate to free the innkeeper and his family. In return, he pledged to pay one hundred zloty, the sum owed by the innkeeper to the magnate. Upon returning to his hometown of Tlust, he gathered his disciples for a feast, during which he spoke again about how the rabbi of Kuty had once presented him with the Zohar, about the joy he had felt that day, and about the importance of putting all one’s trust in the Almighty. The Baal Shem Tov spent a long time expounding the various aspects of this commandment. At the end of his speech, he closed his eyes and sat in silence for close to half an hour. During that time of deep meditation, the Baal Shem Tov heard a voice from heaven commanding him to go to a village near Snyatyn, and there to learn from the local innkeeper how powerful and boundless faith in G*d can be. Then, as if awakening from deep slumber, he told his disciples that he had to go on a journey, and that anyone wishing to join him was welcome to do so.

That same day, the Baal Shem Tov set off for the village accompanied by his disciples who knew nothing about the purpose of the journey. Upon arriving in the village, the Baal Shem Tov came to the inn. The innkeeper ran out to welcome them with a smile of joy, served them a plentiful meal, and prepared rooms for their lodging.

Next morning, after prayers (the Baal Shem Tov always prayed at the crack of dawn), their gracious host served them a breakfast of bread, butter and milk. As soon as the Baal Shem Tov and his disciples sat down to eat, a constable flung the door wide open, and came in, holding a long staff. With long strides, the man approached the table and dealt it three hard blows with his staff. His face was distorted with rage. Without uttering a word, he turned and left the inn.

The scene had frightened the Baal Shem Tov’s disciples. The innkeeper, on the other hand, had watched calmly, as if this were a perfectly ordinary event. The disciples thought the constable must have been drunk, and that the innkeeper was accustomed to his behavior, which would explain his lack of alarm.

At supper, the scene repeated itself. Once again, the same constable entered the inn, gave the table three blows with his staff, and departed in fury.

“What was that?” the Baal Shem Tov asked the innkeeper.

“That was one of the constables working for our magnate, who owns all the villages in the area,” replied the innkeeper. “The magnate has some bizarre customs. When the deadline for paying the rent arrives, he sends this constable to remind each tenant in this strange manner that if he does not pay up before the end of the day, the magnate will place him and his family under arrest.”

After listening carefully to the innkeeper’s words, the Baal Shem Tov asked, “Judging by the fact that you are so calm, you must have the money to pay the magnate. Why are you waiting? Go pay him now.”

“Believe me,” said the innkeeper, “I do not have a penny to pay my rent. Still, I am confident that the Almighty will come to my help as He always does. So there is no cause for concern, and you can eat your meal in peace.”

The disciples went on with their supper, debating Torah issues, expecting that any minute someone – perhaps the prophet Elijah himself – would arrive with a full purse. Thus when the door was flung open, they were certain that they were about to behold the prophet Elijah handing money to the innkeeper. However, it was the same constable standing at the threshold. Once again, he struck the table three times and left in a terrible rage.

The Chassidim were gripped by fear. The day was drawing to a close, and before long the magnate would throw the innkeeper’s entire family in prison! They were amazed to see that the innkeeper was completely unperturbed.

The Baal Shem Tov gave the sign that it was time to say the blessing after the meal. Meanwhile, the innkeeper changed into his Shabbat clothes and left the house.

The Baal Shem Tov and his disciples followed him outside, to see where he was going. The innkeeper walked along the road that led up to a small hill, on top of which stood the magnate’s palace. Suddenly they saw a cart pulling up next to the innkeeper. A man got down from the cart and spoke to the innkeeper; it was clear from their gestures that the innkeeper was objecting to the man’s proposals. A few minutes later, the innkeeper continued on his way. The cart headed back toward the village, but then it turned around, overtook the innkeeper, and the driver spoke to him and handed him some money. The inn-keeper walked on to the magnate’s palace, while the cart turned back toward the village.

When the cart stopped in front of the inn and the driver got down, the Baal Shem Tov asked him, “Tell me, please, what did you talk to the innkeeper about?”

The man recognized the Baal Shem Tov and replied, “I will be honest with you, holy Rabbi. For several years now, I have been buying homemade vodka from the innkeeper. I pay him twenty kopeks a liter. A few times I tried to buy from other producers, and each time I had a stroke of bad fortune. You see, I also lease an inn in a nearby village. I was afraid that he would sell his vodka to someone else, and so I decided to come today and to buy up his entire stock. Just now, when I met him on the road he-demanded twice the usual price. At first I refused, but then, as I sat in my cart, I realized that even at that price the deal was worth it. I turned around and paid him the money, to make sure that he would not sell to someone else.”

The Baal Shem Tov’s face shone with joy.

“See,” he told his disciples, “we thought that to save the innkeeper, I would have to sign a promissory note to pay his debt. Yet the Almighty is perfectly capable of coming to the rescue without my help! That is precisely what I try to teach you: we must put our complete trust in the Almighty. That is why I received divine instruction to come to this village to learn the power of trusting the Almighty from a simple Jew.”

Soon the innkeeper returned holding the magnate’s receipt for the rent payment. The Baal Shem Tov gave the innkeeper his blessing and returned to his home in Tlust. There he found Rabbi Moshe, the Rabbi of Kuty, who had come to thank the Baal Shem Tov for his efforts to ransom the prisoners. He also wished to use the opportunity to see for himself the customs practiced by the Besht’s Chassidim.

The Baal Shem Tov was overjoyed to see his learned guest, and gave instructions to prepare a festive meal in his honor. While the meal was being readied, a cart pulled up next to the house, driven by Rabbi Gershon, the brother-in-law of the Baal Shem Tov. By then, he had recognized the greatness of the Besht, and that studying the Zohar was in accord with the Baal Shem Tov’s knowledge and approach to Torah learning.

During the meal, the Baal Shem Tov recounted to the guests how he had heard a voice from Heaven instructing him to come to a simple person in order to learn boundless faith in the Almighty. Rabbi Moshe then reminded him that, when he had presented the Baal Shem Tov with the Zohar and begun to pray, he had broken into a joyous dance after reaching the words, “Blessed is he who puts his trust in G*d, and G*d will be his pillar of strength.” These words filled the Baal Shem Tov with extraordinary joy. Clasping Rabbi Moshe’s and Rabbi Gershon’s hands, he began to dance. Reb David of Nikolayev immediately made up a beautiful, happy tune, and all the Chassidim joined in the dance. The angels gathered in Heaven to look down upon this dance of joy and faith in the Creator.

The next story also illustrates how the Baal Shem Tov taught faith.

One year the many Chassidim who had come to spend Passover with the Baal Shem Tov noticed that something was amiss. Instead of the usual cheer and uplifted spirits that accompanied holiday preparations, the Baal Shem Tov was visibly saddened and distressed by something.

As a rule, the Baal Shem Tov would be in a state of great spiritual exaltation while leading the Seder,discussing the profound mysteries of the Passover Haggadah. This time, however, he was somber and taciturn, which naturally affected the mood of the guests who had come from near and far. The Chassidim knew that the Baal Shem Tov had a good reason for being in such low spirits, and they too were gripped by an uneasy feeling.

The day before the holiday, following the search for chametz, the Baal Shem Tov gathered ten of his disciples and told them to recite tikkun chatzot with intense concentration. The disciples realized that their teacher was trying to prevent a disaster only he was able to foresee.

As soon as they began reciting tikkun chatzot, one of the Besht’s closest disciples, Rabbi Tzvi the scribe, rushed in to tell them that their teacher was lying on the floor in his room, seemingly unconscious.

Morning came; the disciples hoped that the new day would dispel their teacher’s gloom. Yet the Baal Shem Tov continued to look dejected and pale. He asked the Chassidim to recite their morning prayers as if it were Rosh Hashanah.

After the prayer, the Baal Shem Tov gathered his disciples around him and began to speak words of Torah about faith in G*d, and his conviction that the Almighty would not abandon him in times of trouble.

“True faith in G*d,” said the Baal Shem Tov, “means that even when we see no way of escaping impending disaster, we remain steadfast in our certainty that the Almighty will speedily grant us deliverance.” The Baal Shem Tov added that this certainty is expressed through joy.

From that moment on, the expression on the Besht’s face underwent a dramatic change. It was obvious, however, that this change did not imply that the disaster had been averted – on the contrary, it was meant to avert the disaster.

The Chassidim spent the day before Passover in this atmosphere of mixed and contradictory feelings.

When it was time to bake the matzah that was to be eaten at the Seder, the Baal Shem Tov’s face lit up with joy. He went to the mikveh, then busied himself with baking the matzah. However, once he was finished with this task, he turned to the Chassidim and again asked them to pray minchah with the same awe and devotion as if they were reciting the prayers for Rosh Hashanah.

After the festive evening prayers, which were also recited with intense concentration, everyone waited with both fear and hope for what was to come next.

Finally, the time for the Passover Seder arrived. The pious disciples of the Baal Shem Tov sat around their teacher, anticipating the wonderful words of Torah with which he usually accompanied the reading of the Haggadah. Yet this time the Baal Shem Tov did not raise his eyes from the book. He read the Haggadah without pausing, in a doleful chant. The room was sunk in silence. The Chassidim were lost in deep reflection. Suddenly the Baal Shem Tov laughed. His eyes were shut, his face was radiant; he was suffused with deep inner joy.

Presently he opened his eyes and announced, “Thank G*d! Blessed be He and His holy name! Praise the Lord, who made the people of Israel His chosen people! And Israel, His people, is capable of achieving much more than I, Srolik Baal Shem Tov.”

Joy filled everyone in the room. The Chassidim were eager to find out what had happened, what their teacher had seen with his holy sight. The Baal Shem Tov told them the following story:

On the eve of Passover, the Jews living in a nearby village were threatened by a terrible calamity. The villagers hated the Jews, and they decided to attack them on the night of the holiday. I could see what was about to happen, and I appealed to our Heavenly Father for mercy. I tried to enlist your help as well, in the form of concerted prayer. Yet our combined efforts were of no avail. Then I decided to simply put my trust in our Heavenly Father. I knew the nature of the impending misfortune, and I saw no way to avert it. However, as I already told you yesterday, we must always place our full trust in the Almighty, whatever the situation. This evening, as we sat at the festive meal, my soul could find no rest. The disaster was moving inexorably closer, and rescue was nowhere in sight. Suddenly, the situation changed totally.

In one of the houses in that village, a married couple· was seated at the Passover table. The husband, a Chassid, fairly unversed in the Torah, but an honest and pious man who performed many good deeds, was sitting next to his wife, reading the Haggadah and telling her about the suffering of the children of Israel in Egypt, as described in the midrash.

When he reached Pharaoh’s words, “You must throw every boy that is born into the Nile,” his wife burst into tears.

“Why are you crying?” the husband asked her. “After all, the sons of Israel were eventually saved and delivered from Egypt!”

“If the Lord were to give me a son,” replied his wife, “I would not let anyone touch him! I would not treat him the way the Almighty treats us.”

The husband disagreed, pointing out that the Almighty knows best what we deserve, and that everything He does is rooted in justice.

“But where is His mercy?” the wife continued to complain. “How can He do this to his own sons, the people of Israel? Even if we transgress against Him, we are still His children!”

They continued to argue, the husband defending the actions of the Almighty, and the wife still insisting that He must have mercy on the people of Israel. Meanwhile, an identical debate was being held in the celestial spheres. Each time the woman defended the children of Israel and enumerated their virtues, the angels of good did the same. The angels of evil countered their arguments. I did not know which side would win.

After the fourth cup of Passover wine, the husband ran out of arguments. “You are right,” he conceded. “The Almighty should indeed show more mercy toward His people.” This ended the argument, and under the influence of the wine they had drunk, the two got up from the table and broke into a dance.

“At the same time,” the Baal Shem Tov concluded his story, “the woman’s arguments were accepted in Heaven, and as soon the couple started dancing, great joy spread through all the worlds. I too was filled with great joy. Naturally, the disaster had been averted.”

The disciples listened spellbound to the story told by the Baal Shem Tov. Meanwhile, he took a handkerchief out of his pocket and said, “Hold on to this handkerchief and close your eyes!”

The Chassidim did as they were told, and suddenly they saw the husband and wife dancing their dance of joy at the delivery of the children of Israel.

According to Kabbalah, sparks of holiness are scattered throughout the world. When these sparks are in material objects, by performing a commandment related to such an object, or even reciting holy words of Torah, a Jew fans the fire concealed within these sparks, as it were, thereby elevating these objects and the places in which they are located, bringing them closer to G*d. Every Jew who performs a commandment or utters holy words is instrumental in refining these objects and gathering the divine sparks. He thereby elevates the entire world to a higher level of spirituality. A tzaddik, a Rebbe, serves as a guide, helping the Jew in the performance of this sacred task. The Besht himself, as we have already mentioned, was in the habit of asking each Jew he came across in his wanderings, “How are you?” in order to hear him say, “Thank G*d!” The very mention of G*d’s name frees the sparks of holiness trapped in that place.

After the Besht departed from this world, his followers founded numerous Chassidic centers throughout Eastern Europe. Young leaders, righteous people who symbolized and exemplified a Torah-based way of life, headed these centers. To this day, the Chassidic rabbis who succeeded them continue walking the same path. Some of them descend from the families of tzaddikim and are Rebbes with their own Chassidim; others have been destined to serve as teachers and mentors. (In Hebrew, both are called Admor an acronym of the words adoneinu, moreinu v’rabbeinu, “our master, teacher and Rebbe.”) All of them enjoy special respect and trust, in accordance with the precept of emunat tzaddikim – faith in the powers of the righteous – which is deeply rooted in the Torah. Chassidism has elevated the role of the righteous Rebbe to the highest level, giving tangible form to the Torah idea that the righteous man is the everlasting foundation of the world.

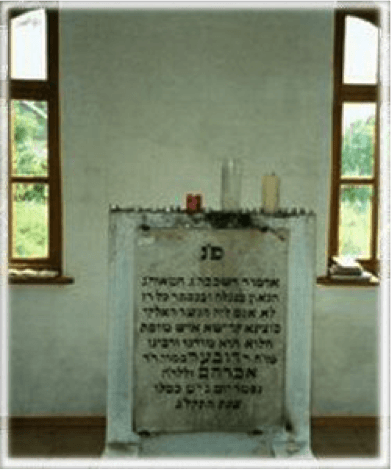

The most famous and respected student of the Baal Shem Tov was Rabbi Dov Ber of Mezherich, known as the Maggid (“preacher”) of Mezherich. A great Torah scholar, Rabbi Dov Ber, before he became a follower of the Besht, had led a secluded life, with little care for material concerns. When he fell gravely ill, he sought advice and help from the Besht, famous for working miracles. The Besht told him that though unable to cure him completely, he could halt the advance of his debilitating leg disease. Thus Rabbi Dov Ber of Mezherich became a prominent disciple of the Besht and a herald of the Chassidic movement.

The most famous and respected student of the Baal Shem Tov was Rabbi Dov Ber of Mezherich, known as the Maggid (“preacher”) of Mezherich. A great Torah scholar, Rabbi Dov Ber, before he became a follower of the Besht, had led a secluded life, with little care for material concerns. When he fell gravely ill, he sought advice and help from the Besht, famous for working miracles. The Besht told him that though unable to cure him completely, he could halt the advance of his debilitating leg disease. Thus Rabbi Dov Ber of Mezherich became a prominent disciple of the Besht and a herald of the Chassidic movement.

The Besht’s son, Reb Tzvi, felt incapable of assuming the leadership of the Chassidic movement, so, following the instructions of his father, who appeared to him in a dream, he willingly yielded this role to Rabbi Dov Ber, who had won the respect and love of the Jewish masses. People flocked to the Maggid for counsel and blessings. Many were attracted by the new leader’s charismatic personality. Rich and poor, Torah scholars and simple folk alike, they came in swelling numbers. Unlike his teacher, the Besht, Rabbi Dov Ber could not travel due to poor health. In order to perfect their knowledge and perform good deeds, thousands of Chassidim came to the new Rebbe; Mezherich became the center of Chassidism, the heart of inspired devotion to the Almighty. The Chassidim preferred to settle next to their Rebbe, and in this fashion the center of the Chassidic movement shifted from Podolia to Yolyn.

At that time – the mid-eighteenth century – Vilna was the major center of Jewish learning, called by the Jews “the Jerusalem of Lithuania.” The Gaon of Vilna, Elijah ben Shlomo, enjoyed absolute authority there. He was famous worldwide not only for his phenomenal knowledge, but also for his profound piety. It so happened that Vilna became the stronghold of the opponents of the Chassidic movement, with the Gaon’s disciples at their head. At first, the rabbis of Lithuania were content with dissociating themselves from the new “sect,” in the hope that Chassidism would not withstand the test of time. However, the passing of the Besht was followed by a surprising development: the popularity of the new movement not only did not wane, but, on the contrary, continued to grow, evolving into a truly popular phenomenon.

The Maggid of Mezherich trained an entire galaxy of brilliant disciples, many of whom became Rebbes, founding various dynasties within Chassidism. Among the most noteworthy disciples, followers, and successors of the Maggid are Rabbi Shmelke of Nikolsburg, Rabbi Ya’akov Yitzchak of Lublin, Rabbi Elimelech of Lizhensk, Rabbi Menachem Mendel of Vitebsk, Rabbi Levi Yitzchak of Berdichev, Rabbi Aharon of Karlin, Rabbi Shlomo of Karlin, and the Maggid of Koznitz. Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liady, the founder of Chabad Chassidism and author of the Tanya was a particularly prominent Rebbe.

The followers’ admiration for the Maggid knew no bounds. Thus, for example, the “hidden tzaddik,” Reb Leib Sarah’s, would say that the reason he went to the Maggid was not so much to learn Torah, but simply to be in his presence and watch him performing the commandments.

The Maggid of Koznitz recounted that before he came to Mezherich for the first time, he had already studied eight hundred books on Kabbalah. Once in Mezherich, however, he realized that he had not even begun to understand Kabbalah.

In 1772, Rabbi Dov Ber departed from this world. Shortly before that, the heads of the Vilna and Brody communities came out with a categorical condemnation of the Chassidic movement. They issued bans against all followers of Chassidism, declaring that the members of the new movement did not believe in G*d, and placing strict prohibitions against eating bread or drinking wine made by them, and certainly against intermarriage with descendants of Chassidic families. Similar proclamations were issued on several other occasions in 1781, 1784, and 1796.

However, even these measures did not seem sufficiently radical to the opponents of Chassidism (called mitnagdim). As early as 1772, a month after the publication of the first ban, a letter was posted from Vilna to all Jewish communities of Eastern Europe. According to that letter, the Chassidim distorted the traditional sacred prayers, and thereby severed themselves from Judaism. “These nonbelievers,” the letter continued, “insert alien words in the prayers, words that are bizarre and false; moreover, they shout these words in such a loud voice that the walls shake. They make strange body movements, and their entire manner is abnormal. And they call all this the flight of the spirit! For these people, every day is a holiday! They neglect Torah studies, ignore learning and erudition, and deny the importance of repentance. Inthe light of the above,” concluded the letter, “we call upon all our brethren, the sons of Israel, wherever they are, be it far or near, to act as befits the keepers of the faith, and to repudiate these heretics. Anyone who fears G*d should distance himself them from!”

Amazingly, the greater the persecutions against the new movement, the more it grew and expanded. All the terrible threats, strict prohibitions, and bans proved powerless against the overwhelming, all-embracing vitality of the Chassidic movement. Chassidism spread like wildfire. Smaller groups of Chassidim merged into larger ones, and regional centers emerged, each headed by the local Rebbe. With time, certain distinctions began to arise between the groups that followed different Rebbes. Some emphasized the importance of reason and understanding (an approach adopted primarily by the Chabad dynasty); others focused on the miraculous powers of the Rebbe (the Belz Chassidim, for example); still others stressed the importance of inspiration during prayer, or the powerful effects of joy and singing.

As a rule, the Rebbe’s title and status were inherited. However, there were many cases in which the Rebbe was succeeded by a prominent and devoted disciple. Sometimes it was the son-in-law of the previous Rebbe, or a more distant relative; occasionally, the successor was a member of the older generation of Chassidim. Usually it was the Rebbe himself who appointed his successor.

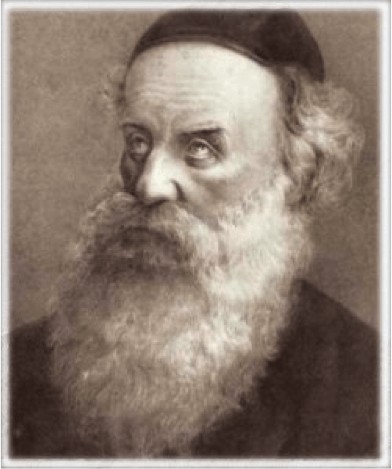

Chabad differed from the other Chassidic movements from its very inception. Although the teachings of Chabad are based on the rational concepts of Chochmah (reason), Binah (understanding), and Da’af(knowledge), the biography of Chabad’s founder, Rabbi Shneur Zalman, is cloaked in mystery; his very birth was accompanied by supernatural portents. According to Chassidism, most of the souls that descend to our material world are sent from heaven to correct sins they committed during their past incarnations. Only in rare cases does the Almighty send down a new soul – exalted, pure, unblemished – entrusted with a special mission for the benefit of the Jewish people. Such was the soul of Rabbi Shneur Zalman, and the Baal Shem Tov knew of its impending arrival, as well as its appointed task: to pave the way for the coming of Mashiach. For reasons known to the Besht alone, he played almost no direct role in raising and educating the boy. Moreover, he forbid Shneur Zalman’s father, Rabbi Baruch, to take the boy along on his annual pilgrimage to the Besht in Medzhibozh. The Baal Shem Tov mentioned Shneur Zalman on only one occasion. “He is not destined to be my pupil. His teacher will be the one who comes after me.”

Chabad differed from the other Chassidic movements from its very inception. Although the teachings of Chabad are based on the rational concepts of Chochmah (reason), Binah (understanding), and Da’af(knowledge), the biography of Chabad’s founder, Rabbi Shneur Zalman, is cloaked in mystery; his very birth was accompanied by supernatural portents. According to Chassidism, most of the souls that descend to our material world are sent from heaven to correct sins they committed during their past incarnations. Only in rare cases does the Almighty send down a new soul – exalted, pure, unblemished – entrusted with a special mission for the benefit of the Jewish people. Such was the soul of Rabbi Shneur Zalman, and the Baal Shem Tov knew of its impending arrival, as well as its appointed task: to pave the way for the coming of Mashiach. For reasons known to the Besht alone, he played almost no direct role in raising and educating the boy. Moreover, he forbid Shneur Zalman’s father, Rabbi Baruch, to take the boy along on his annual pilgrimage to the Besht in Medzhibozh. The Baal Shem Tov mentioned Shneur Zalman on only one occasion. “He is not destined to be my pupil. His teacher will be the one who comes after me.”

Rabbi Shneur Zalman was born in 1745 in Liozna (situated in the Vitebsk area of Byelorussia). He married at fifteen, and following his marriage, Shneur Zalman joined his father-in-law in Vitebsk. Before long, however, he decided to leave his home in search of a deeper understanding of Torah. He had already learned everything that Vitebsk could offer him. At that time, a young man eager to devote himself to Torah study would usually go to the great city of Vilna, to the Gaon’s academy. It is thus not surprising that when Rabbi Shneur Zalman decided to go to Mezherich instead, his father-in-law, a “Litvak” (a common name for residents of historical Lithuania, what is now Lithuania and Byelorussia, most of whom were mitnagdim), was deeply disappointed and frustrated. In his anger, he withdrew all financial support from the young couple. This, however, did not stop Rabbi Shneur Zalman and his young wife. They were firmly convinced that they were on the right path, and that the Almighty would not abandon them. Promising to return in a year and a half, Rabbi Shneur Zalman set out on his journey.

Eventually he reached Mezherich and Rabbi Dov Ber, the Maggid. His initial impression was not very encouraging. The Maggid and his circle failed to meet his expectations. The prayers, and the rituals that preceded them, seemed excessively long, taking up the time he had intended to devote to study. Increasingly, he believed that he had made a wrong decision. Eventually, he resolved to go back to Vitebsk.

However, heaven had a different plan. Shortly after leaving Mezherich, Rabbi Shneur Zalman remembered that he had forgotten something at the synagogue. As he returned to the synagogue, he saw Rabbi Dov Ber surrounded by his disciples. He listened, realized that they were discussing a highly complex halachic issue, came closer, and found himself unable to leave. The profound, elegant and insightful analysis provided by the teacher literally entranced him, and all his earlier misgivings vanished without a trace.

In Mezherich, Rabbi Shneur Zalman developed the central tenets of his philosophy. He was particularly drawn to three fundamental principles: that the human mind, no matter how exalted and pure, is incapable of fully comprehending the Almighty; that man, the crown of Creation, represents a unity of body and soul; and that the ultimate purpose of human existence is to perform G*d’s commandments. These basic principles were the cornerstone on which he subsequently founded the entire system of Chabad philosophy, as described in his great book, Tanya.

When Rabbi Shneur Zalman returned to Vitebsk one and a half years later, as promised, his companions asked him what he had found in Mezherich that was not to be found in Vilna. His answer was, “In Vilna you study the Torah; in Mezherich, the Torah teaches you.” What he meant was that in Vilna, a Torah scholar feels proud and self-important about his achievements. In Mezherich, on the other hand, the scholar’s “self’ is relegated to the background, eclipsed by the dazzling greatness of Torah.

For a number of years, the married couple lived in dire poverty. Finally, in 1767, Rabbi Shneur Zalman was offered the position of preacher in Liozna. From that time on, the authority of Rabbi Shneur Zalman (otherwise known as the Alter or “Old” Rebbe) steadily increased. Three years later, the Maggid of Mezherich entrusted Rabbi Shneur Zalman with the task of re-editing the Shulchan Aruch – the Code of Jewish Law. The main innovation in the resulting work was that it provided a brief outline of the underlying reasons and significance of each law, as well as a selection of practical guidelines gleaned from among the numerous and at times contradictory interpretations offered by the great law-givers, among them the Rambam, the Rosh, and the Beit Yosef. Inaddition, Rabbi Shneur Zalman cited an extensive list of sources and references for every law. This was an enormous task, requiring extraordinary knowledge of the Talmud and practical Halachah. Furthermore, a great deal of decisiveness and self-assurance were needed in order to resolve the thorny issues over which the aforementioned authorities held dissenting opinions.

This new edition of the Shulchan Aruch, except for the first part, was published after Rabbi Shneur Zalman departed from this world. This book has been accepted and acclaimed by the entire Jewish people, not by Chabad Chassidim alone. It is known as the Shulchan Aruch HaRav (the Rabbi’s Code of Law).

After Rabbi Dov Ber, the Maggid of Mezherich, left this world, his son Rabbi Avraham (known as the Malach, the “angel”) declined the role of Rebbe. Three of the Maggid’s most prominent disciples – Rabbi Menachem Mendel of Vitebsk, Rabbi Avraham of Kaliska, and Rabbi Shneur Zalman – separated, each going to a different location with the pledge to spread the Chassidic philosophy wherever possible. Rabbi Shneur Zalman inherited the formidable undertaking of introducing Chassidism to Lithuania, the stronghold of the mitnagdim. Despite all the obstacles, he succeeded in this task. Among other things, he established religious schools for young men with outstanding ability.

His path was fraught with difficulties. During his travels, he was often forced to go into hiding to evade persecution. Once Rabbi Shneur Zalman was invited to a halachic debate against a select group of mitnagdim. To the great disappointment of his adversaries, he astonished everyone present with his extraordinary mastery of the Talmud. In a letter preserved from that time, one of the people present at the debate wrote that after the talk given by Rabbi Shneur Zalman, over four hundred of the most illustrious Torah scholars joined the Chassidic movement, many of them following him to Liozna.

The Rabbi’s popularity and admiration for his righteousness and knowledge were so great that the number of people flocking to Liozna grew with each day, until he was compelled to issue “the Liozna rule,” limiting the number of visits the Chassidim could pay to their Rebbe.

The Tanya – the Alter Rebbe’s major work – was first printed in 1797. Hundreds of handwritten copies had circulated throughout the cities and towns of the Russian empire. However, repeated copying of the book had led to an unacceptable number of errors, so the Alter Rebbe saw the need to print it. At its core, the book is a revised version of the answers given by the Alter Rebbe to the questions asked by Chassidim during personal counseling sessions.

The Tanya fuses together the nigleh (“revealed”) aspect of Torah, based primarily on the Talmud, and its sod (“hidden”) part, drawing on the Kabbalah: the Zohar, the teachings of the Holy Ari, Rabbi Moshe Cordovero, and other Kabbalists – but it is primarily based on the teachings of Rabbi Israel Baal Shem Tov and the Maggid of Mezherich. The Tanya was written for those seeking and thirsting for knowledge, but not for confused individuals, entangled in the web of philosophy and skepticism, for whom the Rambam had written his famous Moreh Nevuchim (Guide for the Perplexed) six centuries earlier. The Tanya was intended to reach, and did reach, simple and sincere people of unshakeable faith, who were searching for new, better ways to serve the Almighty.

The Tanya (named after the first word of the book), also known as Likutei Amarim (Collected Discourses), presents the substance of Chabad philosophy. As implied by the word “Chabad” (an acronym of the Hebrew words Chochmah – Binah – Da’at (reason – understanding knowledge), this philosophy emphasizes that it is incumbent upon us to use the rational power of the intellect to strive for knowledge of G*d and His entire creation. At the same time, Chabad constantly reminds us of the limitations of human reason, which can never achieve complete understanding of the Creator or fully grasp how the material world was created out of pure spirit. Devotion to the Almighty, based on awe and love, must be preceded by rational awareness of the principle of Permanent Creation (based on the Baal Shem Tov’s teaching that the Almighty constantly recreates and sustains the existence of every object and every living creature), as well as the idea of omnipotent Divine Providence. This awareness can and does lead Jews to experience fear and love of G*d, at least at the lowest level of fear and love. All of this does not in any way contradict the concept of the ultimately unknowable nature of G*d.

The Tanya explains in detail the concept, which is of paramount importance, that each Jew possesses two souls: the nefesh elokit (godly soul), which partakes of G*d’s essence, and the nefesh bahamit(animal soul). Naturally, the former strives toward virtue, light, holiness. The latter also has the faculties of reason and emotion, and is as capable of striving for positive goals as the godly soul, yet it is equally capable of exercising its base instincts by striving for earthly rewards and pleasures. These two souls wage a constant battle with each other. G*d, true to the principle of free choice, does not intervene in this battle, although He naturally wishes to see the godly soul be victorious, for by conquering the animal soul and raising it to virtue, light and holiness, the nefesh elokit accomplishes the purpose for which it descended into this corporeal world.

People are divided into the righteous, who have totally subdued the animal soul, or even converted its brute power into virtue, and the wrongdoers who are ruled by the animal soul. Inbetween these extremes is the beinoni (“intermediate”) person, the actual subject of the entire Tanya, who, though he has never actively violated a commandment, has never succeeded in fully taming his base instincts. An ordinary person is not expected to become a saint, but he is able and required to reach the beinonilevel, hence the appeal to do teshuvah – to return to one’s source and to remember one’s purpose. Universal teshuvah will bring about the coming of Mashiach and the attainment of the ultimate goal of Creation – the establishment of the kingdom of light, goodness, and truth, in which G*d will be a tangible, visible presence.

As mentioned above, the Alter Rebbe’s Tanya is a remarkable synthesis of Talmudic knowledge and Kabbalistic teachings. Those who succeed in studying Tanya in depth become permeated with the understanding that there is nothing but the Almighty. The minds of the Rebbe’s Chassidim were occupied with the new teachings even while they were engaged in the most mundane chores of daily life. The story is told that Rabbi Binyamin Kletzker, one of the Alter Rebbe’ s most devoted Chassidim, was so preoccupied with thoughts about the Creator that while filling out a report on his financial affairs, he wrote in the “total” column: Ein ad milvada (“There is nothing but the Lord!”).

The extraordinary popularity of the Alter Rebbe added fuel to the fires of jealousy and enmity. Two years after the publication of the Tanya, he was arrested on charges of treason against the Russian empire. The pretext for the denunciation was the fact that the Rebbe collected funds to support the needy in the Holy Land, which was part of the Turkish Empire at the time. Since Turkey had been at war with Russia for many years, he was accused of abetting an enemy of the czar. The Alter Rebbe was arrested and imprisoned in the Peter-Paul fortress in Petersburg.

Chassidim recount that the Rebbe was arrested in Liozna on a Thursday, put in a horse-drawn carriage, and sent to Petersburg under close guard. The next day, with only a few hours left until the start of Shabbat, the Rebbe asked the officer in charge of the guards to delay the trip until after Shabbat. The officer categorically refused. They continued on their way, but a short time later one of the carriage’s axles broke. There was no choice but to stop and send for a blacksmith from the nearest village. Soon the axle was fixed, and the journey resumed. Suddenly, one of the horses collapsed and expired. The guards were gripped by fear and confusion; still, anew, fresh horse was brought instead. However, no matter how hard the horses strained to move the carriage, it would not budge an inch. By then, the officer himself was terrified. He told the Rebbe that they would stop for the night in the nearby village, but the Rebbe refused his offer, worried that they would not reach the village before sunset. Eventually, they pitched camp in the woods by the side of the road. As soon as Shabbat ended, the journey continued without any further mishaps.

At the fortress, despite hours of relentless questioning, the investigators found nothing to substantiate the charges against the Rebbe. As the investigation wore on, the interrogators became increasingly impressed by the Rebbe’s extraordinary personality, his brilliance, and his boundless erudition in every area of knowledge. His cell became the site of frequent visits by top government officials. By some accounts, the czar himself paid a visit to the Rebbe. He came incognito, wearing plain clothing, and tried not to do anything that would betray his true identity. Even though the Rebbe had never seen the czar, and photographs did not exist at the time, he recognized him at once and treated him with every honor that the Torah instructs one to exhibit toward a monarch. The royal visitor was fully as impressed as his subjects by this unusual prisoner.

On several occasions, the Rebbe was interrogated at the Senate, situated on the other bank of the Neva River. He was transported by boat, usually at night. During one trip, the Rebbe asked the officer of the guards to stop the boat so that he could recite the blessing for the new moon. The officer flatly refused. “If I wanted to,” said the Rebbe, “I could have stopped the boat by myself.” True enough, the boat slowed to a stop. The officer was gripped by spine-chilling fear, yet he persisted in his refusal to allow the Rebbe to recite the prayer. Once again, the boat started to move. After momentary reflection, the Rebbe repeated his request. This time the officer agreed, on the condition that the Rebbe gave a written blessing to him and his descendants. The sixth Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak, wrote that when he was a child being told this story about the Alter Rebbe, he wondered why the Rebbe had sought the permission of the guards in order to recite the blessing, rather than do so as soon as he had stopped the boat through his supernatural powers. Only later, after Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak had plumbed the depths of Chassidic philosophy, did he realize that the Alter Rebbe needed the guards’ assent because the commandments must be observed as part of the natural course of events rather than through the agency of miracles.

Fifty-three days after his arrest, the Rebbe was completely exonerated and released. The joy of his followers was so intense that it affected many Jews who had not been exposed to Chassidim and the Rebbe until then. Many of them saw the hand of G*d in his liberation. Thus the slanderers’ intrigues not only failed to bear fruit; they actually backfired, increasing the popularity of the Rebbe and the Chassidic movement tenfold. The 19th of Kislev, the day of the Rebbe’ s release, was declared a holiday by Chabad Chassidim, and became known as the “New Year of Chassidism,” or the “Holiday of Deliverance.”

Nevertheless, the Rebbe’s ordeal was far from over. He was arrested again two years later on new fabricated charges, and was forced to defend himself before the czarist court. This time he was allowed to debate one of his accusers, a rabbi from Pinsk. Their polemic was held in Yiddish, and went on for many hours. Naturally, the judges could not understand a single word. When the debate ended, the court told the Rebbe and his opponent to sum up their arguments in written Russian. Meanwhile, Czar Paul was assassinated and succeeded by Alexander I. Shortly after the coronation, the new czar, eager to win the loyalty of his subjects, including the Jews, dismissed all charges against the Rebbe.

The Rebbe did not return to Liozna. He moved to the neighboring town of Liady, intending to establish a new center of Chassidism. He spent the next ten years of his life in Liady. During that period, he invested great effort in improving the living conditions of Jews throughout Russia. One of the primary purposes of his special fund for the needy was to provide aid to Jewish refugees left destitute by the persecutions of 1804, when Jews were expelled from their homes after being accused of selling vodka to the peasants and causing them to stop working.

In 1812, when Napoleon’s army invaded Russia, many Jewish leaders, attracted by Napoleon’s promises of equality and freedom, and particularly his stated intention to grant the Jews all the rights and freedoms they had yearned for, prayed for the victory of the French. However, the Rebbe could foresee the consequences of this freedom. He saw that if the French won, the economic position of the Jews might improve, but their spiritual condition would suffer. If, on the other hand, the Russians won, the Jews would suffer economically – in fact, they would be persecuted but the Jewish spirit would flourish. The Rebbe therefore supported the czar, doing everything in his power to bring about Napoleon’s defeat, for he feared that if Napoleon were victorious, the consequent emancipation of the Jews would lead to mass assimilation.